Chimpanzees did not mate with pigs and produce humans.

| |

|

|

| Adorable piggy, by A R, via Wikimedia Commons |

|

| I am not a little piggy! |

I was surprised that a group of anthropologists would even consider this a reasonable topic for discussion, but perhaps this speaks to the need for more cross-discipline communication.

I find it distressing that the chimp-pig hybrid article dismisses the abundance of genetic evidence that provides no support for such a hypothesis of human ancestry. There are several scientific and logical flaws with the supposition that humans resulted from what must have been multiple matings between chimpanzees and humans. Also, please see an alternative discussion of this hypothesis by PZ Myers here, then another summary and discussion by ARTIOFAB here.

There are no regions of our genome where the genomic content more closely resembles a pig than a chimpanzee. If such a hybridization had occurred, we would, like we do with the Neandertal and Denisovan genomes, find regions where segments of modern humans are more closely related to pigs than any other species, but we do not.

I really don't understand how anyone can look through images of pigs and think that we resemble pigs more than we do chimpanzees or bonobos:

|

| Pan paniscus (bonobo) By Pierre Fidenci (http://calphotos.berkeley.edu), via Wikimedia Commons |

2. Body hair has been lost independently in many mammalian lineages.

Yes, hairlessness over most of our bodies evolved in humans, but it did so independently in the human lineage. Similarly hairlessness independently (we call it convergent evolution) evolved in naked mole rats, manatees, and cetaceans (dolphins and whales). Rodents are actually more closely related, evolutionarily, to humans than pigs, but we don't see a naked mole rat - chimp hybrid theory because it is obviously ridiculous to the general public. The chimp-pig hypothesis is even more improbable. And, furthermore, many pigs have not lost hair on their bodies or faces.

|

| Bearded Pig, by Art G. from Willow Grove, PA, via Wikimedia Commons |

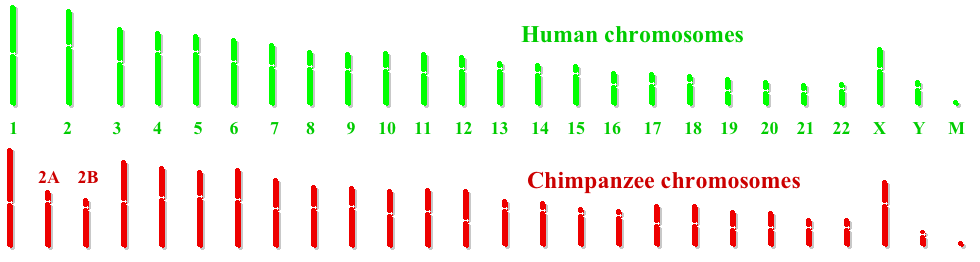

3. Chromosomal and genetic differences between chimpanzees and pigs preclude fertile hybrids.

The chromosomal differences between chimpanzees (48) and pigs (38) would preclude any chimp-pig zygote from developing, or even replicating properly. The author greatly over-exaggerates claims about the fertility of hybrids of sheep-goat hybrids (most are stillborn), and also misuses the term geep (which refers to a chimera of sheep/goat cells). The author also ignores the close evolutionary relationship of sheep and goats, where the chromosomes (and the breaks/fusions) can readily be mapped, where most of the gene content is still conserved among chromosomal regions. Such an identity of the order and orientation of gene content does not exist between chimpanzees and pigs, but is possible between the very closely related human and chimpanzee (all chromosomes are one-to-one, except for human chromosome 2, which is a fusion of two ancestral chromosomes that remained unfused in chimpanzee).

|

| Mapping of human and chimpanzee chromosomes, by JWSchmidt, from Wikimedia Commons |

4. Fossil evidence can account for all of humans ancestry to the human-chimp common ancestor.

At what point in time would this have occurred? Certainly not the present. We have fossil evidence of modern humans, ancient humans, ancient hominids, ancient apes, ancient monkeys, and so on. Science can account for the progression of humans from our shared ancestor with chimpanzees, and even further back. At no point in history do the fossils of ancient humans in any way resemble the fossils of ancient pigs.

5. Modern species share common ancestors, they did not beget each other.

Modern humans did not evolve from modern chimpanzees any more than modern chimpanzees evolved from modern humans (that is, not at all). Fossil evidence suggests that the chimp-human common ancestor looked a lot more like a modern chimpanzee than it did a modern human, suggesting many more physical changes along the human lineage, but the modern chimpanzee has also experienced changes since our most recent common ancestor together, approximately 6 million years ago. Both humans and chimpanzees share a common ancestor with pigs about 90 million years ago.

6. Domesticated pigs and chimpanzees do not live in the same locations.

Pigs (with reduced body hair) were domesticated in East Asia and in Europe. Chimpanzees live in central Africa. They live on different continents. They did not ever have the opportunity to get busy. Wild boars can be found in northern Africa, but this is still quite far from where chimpanzees live, and if they do overlap in range, it is only a very recent occurrence.

|

| Wild Boar, by Volker.G (Own work), via Wikimedia Commons |

You could attempt each of the possible combinations (chimp sperm with pig eggs, and pig sperm with chimp eggs) and test the viability. It it works, we can have this discussion. If not, this guy needs to stop spouting nonsense that detracts from the real science being done.

|

| By David.Monniaux, via Wikimedia Commons |

3 comments:

So, I skimmed this guys website... interesting. While he has a PhD (as he makes clear on his website), he seems to have completely divorced himself from the academic community.

For instance, there's no CV, and no description of ongoing (direct) research. There's no indication that he's trying to produce academic-style reports of any research. Instead, the website emphasizes a lot of scholarship he's done on topics that he seems to have no direct experience with. It seems that he's abandoned all rigor in his scholarship and given up on engaging with other researchers.

There isn't even any indication that he has attempted to perform any hybridization experiments on any animal.

Given that this guy did a bioinformatics thesis (identifying LTR transposons in Mouse and Rice genomes), he should at least be able to find something interesting in published genome sequences... but there's no sign of any real research on his website.

If anthropologists are taking him seriously, I would like to know why.

Exactly. I really don't understand his motivation.

I think the Anthropology Network I joined is a very diverse group that includes people with training as anthropologists, and those without formal training, but an interest in anthropology. Unfortunately, it doesn't seem as if anyone with any training chimed in on this link. I was very surprised.

This comment was sent to me by Gregory A. Whitehead:

Regarding the anthropology group, give them time, more serious comments will follow, albeit slowly. The problem, in my view and apparent from comments, is that anthropolgy has been dominated by the culture academics, much akin to sociology, while the science of field research and technologies has accelerated in recent years. Napoleon Chagnon made quite a stir when he broke from tradition and made research claims based on biology in his studies of Amazonian tribal behaviors. His work has been vindicated in recent times but the overall mind and skill set is still lacking to grasp rigorous quantitative paleogenetics. This is why your work and that of anthropolgists like John Hawks is so refreshing and critical to our times. It seems we are making and refining new discoveries every day.

The pendulum will swing with new generations of applied scientists coming on in the fields of anthropology and archaeology. Meanwhile, culture, a soft associative approach, seems to dominate the discipline.

Post a Comment